Long before he was a Golden State Warrior, Gary Payton II got an ultimatum.

Option A: He could get a sports scholarship to fund his potential higher education. Option B: He could forgo a college degree altogether. In high school, Payton, as he summed it up simply, “wasn’t the best student.” His educational struggles translated to disinterest in school. It mistakenly forced doubts in his intellectual capacity.

This was the oblique data which informed his dad’s — NBA hall of famer, Gary Payton Sr.’s — objection to paying for his son’s college.

“I decided,” Payton II said in a Zoom interview, “to throw all my eggs into working on my basketball game.”

It wasn’t that Payton was a bad student through school. It wasn’t that he slacked off. It wasn’t a deficiency of intelligence, as was at times incorrectly assumed. It certainly wasn’t a lack of resources.

Payton is dyslexic.

As many as one in five students, according to Yale research, suffers from dyslexia, a learning disability with a spectrum of issues and severity. Dyslexia impacts how the brain processes language in written and spoken form. The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity defines it as an unexpected difficulty in reading for one who has the intelligence to be a better reader. According to the Yale Center, it is the most common of all neuro-cognitive disorders. It complicates reading and spelling — fundamentals present in almost every scholastic subject.

Trouble matching letters to sounds and alphabetic combinations to words, though, isn’t dyslexia’s biggest hindrance. It’s the self-esteem it erodes. It’s the way dyslexia confuses a difference in learning for feeblemindedness. A confusion maintained by the affected and those around them. This is especially true in college, where the worth of students is connected directly to their ability to comprehend.

According to the Data Mart of the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, a total of 11,559 students attended Las Positas College during the 2023-24 academic year. Of them, 631 registered with the school’s Disability Students Programs and Services (DSPS).

ADHD was diagnosed in 22.5% of the registered students. Another 25%, or 158 students, are listed as having a general “learning disability” (LD). Dyslexia falls under this umbrella.

LPC’s DSPS Director, Christopher Crone, said that with dyslexia “there is often overlap – comorbidity if you will.”

That 80% of people with learning disabilities are dyslexic — per Yale — and it’s still obscured under the generalized LD label illustrates dyslexia’s shortage of visibility. And if 20% of the population is dyslexic, that suggests closer to 2,300 students on campus are impacted.

“Truth About Dyslexia” podcast host Stephen Martin said that dyslexics in higher education are vulnerable to feeling dumb despite their elevated intelligence. Having graduated from the separation of classes enforced by high school-level special education programs, dyslexic students are left comparing themselves to unaffected peers.

“Many dyslexics have high IQs,” Martin said, a New Zealander with dyslexia who created the podcast to heighten awareness. But it’s how they process the information in their head, and output it in the real world. Getting their big visions and what they can create onto paper can be a huge pain.”

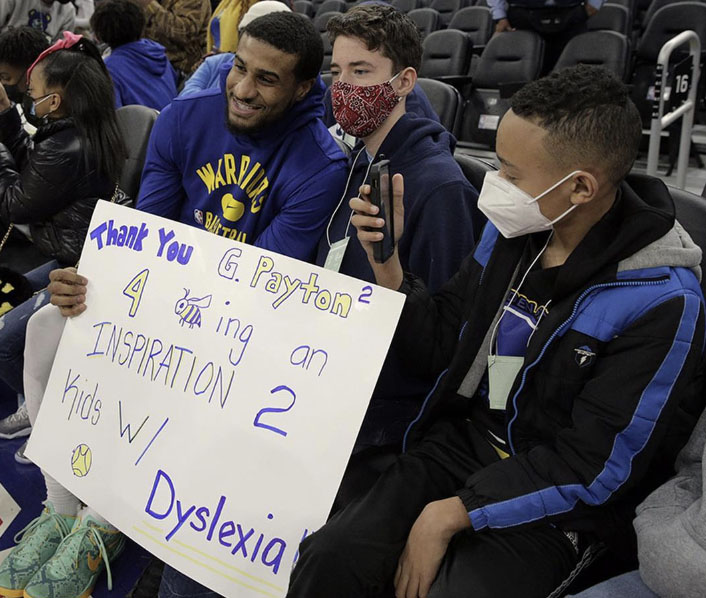

GP (HAS IT) 2: After battling dyslexia, Golden State Warriors star Gary Payton II is now an advocate and inspiration for youth with the condition, as seen here with a couple of fans at Chase Center in San Francisco. (Photo courtesy of the Golden State Warriors)

It’s like if a left-handed person were forced to write with the opposite hand — and when the words inevitably look sloppy, it’s assumed they’re less competent.

When their educational needs are properly met, dyslexic students might even be disproportionately talented. They’re often “twice-exceptional,” according to Jessica Romo, a DSPS counselor and learning disability specialist on campus.

Twice-exceptional, as she put it, is code for disabled and gifted. Like dyslexic polymath Leonardo Da Vinci. And relativity-theorizer Albert Einstein. Or like how a dyslexic Gavin Newsom can ascend to Governor of California. Or how Payton II can process high-level defensive schemes for his suffocatingly masterful on-ball pressure.

Payton no longer struggles with confidence. He learned his condition wasn’t a fatal flaw. He got the tools needed to matriculate at school, earning an associate’s degree in business from Salt Lake Community College and a bachelor’s degree in human development and family services from Oregon State.

“Once I started to learn that I have my own way of learning … then that’s just putting in the extra work at home and class,” Payton said. “But being ready for that next class, being prepared for that pop quiz or whatever you’ve got, you just have a different swag to you.”

Of course, making the NBA, with its requisite fame and fortune, works wonders for one’s swag.

But remembering the young man he was, the one confused by false convictions of dullness, Payton works to relay confidence through his transparency. He knows, from experience, many need it.

Jaden Griffin needed it.

Griffin is a sophomore journalism major at Las Positas. He was nine the first time he saw letters move.

His undiagnosed dyslexia became a personal enigma of epic proportions. And Griffin had a coexisting stuttering problem — related, retrospectively, to his disability. Social, cultural and educational stigmatization followed. His kid-aged classmates teased Griffin’s perceived inability.

“I didn’t know what was going on with me,” he said. “I’d see words moving. I was trying to read it, just crying with frustration.”

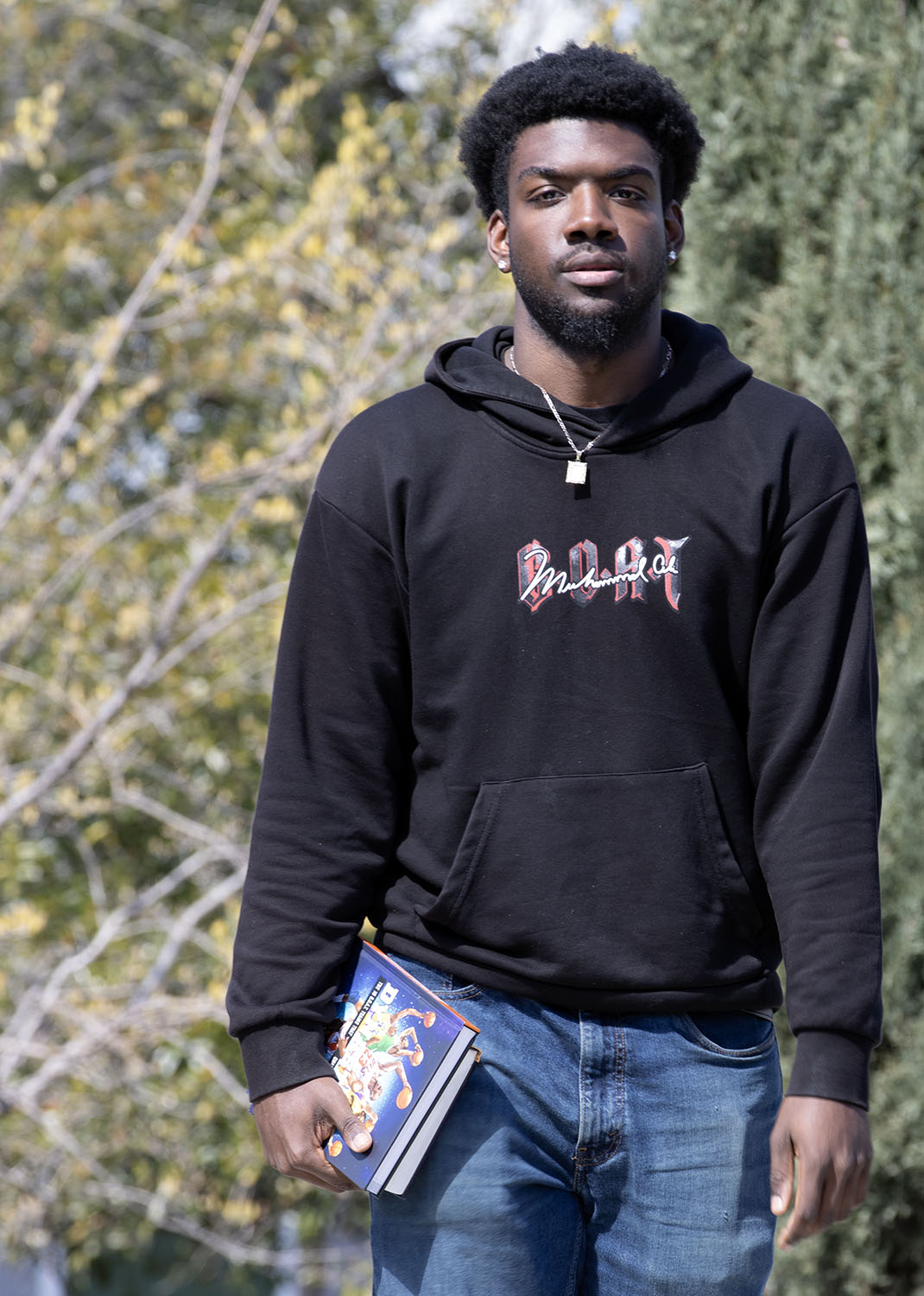

NOT DEFEATED: Jaden Griffin was once worried if he was “stupid” after being diagnosed with dyslexia. But his confidence is higher now with the understanding he just learns “differently.” (Photo by Angelina An/ The Express)

That kind of frustration is one of many reasons advocates press for the early identification and intervention for dyslexia. The younger a child is when dyslexia is realized and diagnosed, the sooner the child can reach their full potential — the sooner it’s clear to them that different doesn’t mean deficient. In light of 50 years of extensive scientific research surrounding dyslexia, some argue educators should be able to recognize its signs in young students.

“Such early identification,” University of Oxford professor Maggie Snowling wrote in the National Library of Medicine in January 2013, “should allow interventions to be implemented before a downward spiral of underachievement, lowered self-esteem and poor motivation sets in.”

During a conference with his parents, Griffin learned from his eighth-grade history teacher he might be dyslexic. A formal diagnosis confirmed it.

It confirmed his intelligence, too. He wasn’t dumb. He never was. Still, Griffin was initially disappointed with the diagnosis.

“I was like, ‘Man, I’m stupid or some shit?’ I’m really not,” he said. “I just learn differently.”

Gradually, he got more help in school. He read more books. He learned that to better comprehend material, he couldn’t be exclusively told the information — he had to see it in action, too. Sureness of intellect took time and consistency and patience.

In high school, he had an Individualized Education Program (IEP). The programs are documents outlining the educational needs of a disabled student. Covered by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the plans are written under the purview of the student’s guardians and school district. In California during the 2022-23 academic year, 14% of public school students aged 3-21 were served by IDEA.

Griffin’s IEP gave him essential educational assistance but also meant he’d be in separate classes. Romo said this separation from the general student population can feel depreciatory. It helped “for a bit,” Griffin said, “but it really didn’t help us reach our full potential.”

He feels like high school failed students with disabilities. The school system didn’t, to Griffin, teach independence or accountability. It instead followed the “tell you to do this and that, and if you don’t, call your parents” model, he said. He thought community college would be easier.

It was.

The Las Positas College classrooms Griffin occupies are places of intellectual surety. For one, he’s entirely accountable for himself. Secondly, his personalized accommodations — such as extra hours on quizzes and tests and an AI tool that can read printed books back to him — are all confidential. He’s completely immersed alongside and held to the same expectations as any peer in any class he takes.

Today, in his second year at LPC, Griffin is “way more confident with my intelligence,” he said. He plans on transferring to either UC Davis, University of Nevada Reno, or University of Arizona.

An audible seriousness stole his typically buoyant tone of voice. Asked about the advice he’d give to dyslexic kids, Griffin seemed for a moment to think of himself — of the teased kid crying in frustration, unable to interpret the meaning of moving words.

“Take your time. It’s OK,” he said. “You’re not stupid, you just learn a different way. Over time, you will overcome it – it just takes a lot of patience, time and just being consistent.”

***

TOP PHOTO: Dyslexia hampered the confidence of Jaden Griffin, as his condition made reading difficult and fostered feelings of inadequacy. But Griffin is not alone as 20 percent of Americans suffer from dyslexia. (Photo illustration by Camille Leduc/ Photo by Angelina An/ The Express).

Olivia Fitts is the News Editor and Opinions Editor for The Express. Follow her on X, formerly Twitter @OLIVIAFITTS2.