Dyrell Foster was smiling.

It wasn’t the expression one would expect from the leader of a school that has been shut down by a global pandemic. But when he logged into ConferZoom for an interview with The Express, a beaming grin stretched across his face. His dark blue polo shirt with dark rimmed glasses were less official-looking than his usual suit, tie and freshly shaven face. He wasn’t in an office surrounded by plaques and certificates, with pictures of his family on a wooden executive desk. Instead, he was sitting at the kitchen table in his home. His family was visible in the form of his 8-year-old daughter, Maylea. In a pink shirt with a ponytail dangling down her back, she opened the fridge then grabbed a plate from the cabinet, not even realizing she was in the video frame of her daddy’s interview. Eventually she noticed, the surprise evident in her raised eyebrows, and quickly scurried out of sight.

“Things are different now,” Foster said. “I’m really just adjusting to this whole situation and kind of settling in, finding my groove.”

After more than 15 years working his way up the administrative ladder — from director of student life at Mt. San Antonio College, to dean of student affairs at Rio Hondo College, to vice president of student services at Moreno Valley College — Foster is now president of Las Positas College. On Feb. 10, an HD-clear 70-degree Monday, he arrived on campus for the first time as the leader of the college. It was his time, the next step on his journey. He was so focused on getting acclimated to his new kingdom that when he read something about the new coronavirus, he initially didn’t think of it as much more than an interesting current event.

Unbeknownst to anyone, the first COVID-19 death happened in Santa Clara County just days before Foster’s start date. So it was already in the Bay Area. Five weeks later, it would shakeup Foster’s presidency in a way he could have never imagined. The campus was closed by March 17 and what was already a challenge, leading a community college, suddenly became monumental. Stakes that were already high were raised to life or death.

Circumstances don’t make a person, they reveal a person. The Greek philosopher Epictetus is credited with that catchy, inspirational quote. It would suggest Foster is about to be revealed. His first task at his first job as president is to guide LPC through a pandemic. The future of the school is, on some level, in his hands as it navigates these unforeseen waters. LPC will have to adjust to new times, adapt to new realities, in order to remain a beacon of higher education at this level.

On one hand, this is not what he signed up for when he inked his three-year contract that pays $215,000 per year. Who could have known he was walking into a global crisis? On the other hand, this is exactly what he signed up for — to lead. Perhaps, if fate was at play, this is why he was chosen, because he might be more ready for this than even he knows. Perhaps that’s why he can smile.

“During these unprecedented and uncertain times,” said Sherri Moore, executive assistant to the president, “I find myself thankful that Dr. Foster was the choice for President of Las Positas College.”

Prior to Foster starting his position in February, he connected with Roanna Bennie, who had served as interim president of the college since Barry Russell initially stepped aside for health reasons the summer of 2017. Bennie was in a similar situation starting off because LPC was also her first time filling the shoes of president, though Foster came from the student services world and Bennie came from the academic services world. She gave him the lay of the land, the context of Las Positas and its inner mechanisms.

“I remember how patient and how willing he was to listen,” Bennie said, perhaps partially expecting him to jump right in and figure things out on his own.

“I just appreciate,” Foster said, “all the time that she gave me and for supporting me during my transition.”

Before the campus closure, Foster was living at Larkspur Landing, an all-suite hotel located just south of Interstate 580 in Pleasanton. His family remained in their home in Southern California until his wife of 11 years, Tammy, a communications specialist currently working in governmental affairs, was able to find a job closer to the campus.

Foster filled the absence with FaceTime calls. His face lit up and his lips curled into a grin as he talked about those weekly visits.

“On the weekends we would choose to go have brunch somewhere,” Foster said. “We would typically take the kids out on hikes and just be active.”

Foster was just getting settled on campus, matching names with faces. One of the faces he saw often was Jakob Massie’s — the student trustee for LPC. Massie served as a bit of a transition aid for Foster. They attended multiple meetings together and collaborated frequently.

Foster impressed Massie initially when he made time to sit down with various members of LPC Student Government to get their perspective and learn of any concerns and initiatives. Members of student government, according to Massie, are accustomed to a disconnect between students and the school’s administration. But Foster felt like an instant change in that regard.

“I had heard many great things about him from my friends and colleagues at Moreno Valley College,” Massie said. “President Foster instantly came off as a very pleasant and caring individual. He has definitely lived up to his praise.

“He truly cares about the students at our campus and I’ve seen him play an active part in many of our college’s governance committees, attending to learn about our campus culture and understand his new environment so that he can complete his duties as best as he can.”

That was a common impression Foster made out of the gate.

“He is very authentic, considerate, and thoughtful,” Moore said, “and leaves one with the impression that he is here to serve us and the students. Dr. Foster encourages administrators, faculty and staff to provide input on decisions that may affect them or ones on which they have expertise. He demonstrates a high level of respect and actively asks for their input or questions they may have. Then he truly listens to what is being said.”

Foster arrived at a booming LPC. The campus upgrades included a new field and plans to tear down old buildings for new, state-of-the-art ones. thanks to Measure A. California Governor Gavin Newsom had also proposed a larger budget for higher education, which would help benefit LPC’s enrollment and investments for student success.

But priorities shifted when COVID-19 took over.

Figuring out graduation in the midst of shelter-in-place orders and how to provide financial assistance to students in need was just the tip of the iceberg when it came to the issues LPC had to solve. Leaders had to figure out how to get students the proper materials to thrive online, such as laptops and wifi hotspots. Perhaps the most concerning matter would be deciding on when the campus would reopen to students and faculty. While it was decided that the summer semester would be completely online, there is an ongoing debate over whether the campus will reopen in the fall. The school is preparing for three semesters of distance education only, just in case.

“We’ve been dealing with issues that have come up that we aren’t necessarily prepared for,” Foster said, “and having to respond.”

With the school closed, Foster was cleared to return home — which he did on April 4 — until the campus reopens. Since then, he’s been running the college from Southern California.

When Tammy found out he was coming home for a while, she decided to clean out a closet in their home to use as an office. With one computer and limited space, Foster and his wife take turns using the makeshift office for various video conferences and work. When both need to work, well, one of them has to use the kitchen table.

His day is full of ConferZoom meetings, about school business and some relating to navigating the COVID-19 pandemic. He has daily calls with Chabot College President Susan Sperling and Ron Gerhard, now Chancellor of the Chabot-Las Positas Community College District. The three heads keep their finger on the pulse of the campuses, discussing and incorporating what’s being handed down from governmental agencies and authorities while addressing the issues coming out of each college.

Foster said he leans heavily on Moore and Kristina Whalen, LPC’s Academic Vice President. And the advice and insight from Bennie he received has proven especially valuable once everything changed.

Like other working people, Foster doesn’t have to compute travel times into his schedule, or even the walk from meeting to meeting, building to building. The next thing is just a few clicks away.

“There’s not necessarily a lunch built into my calendar either,” he said, chuckling while rubbing his thumb on his eyebrow.

Foster is smiling again.

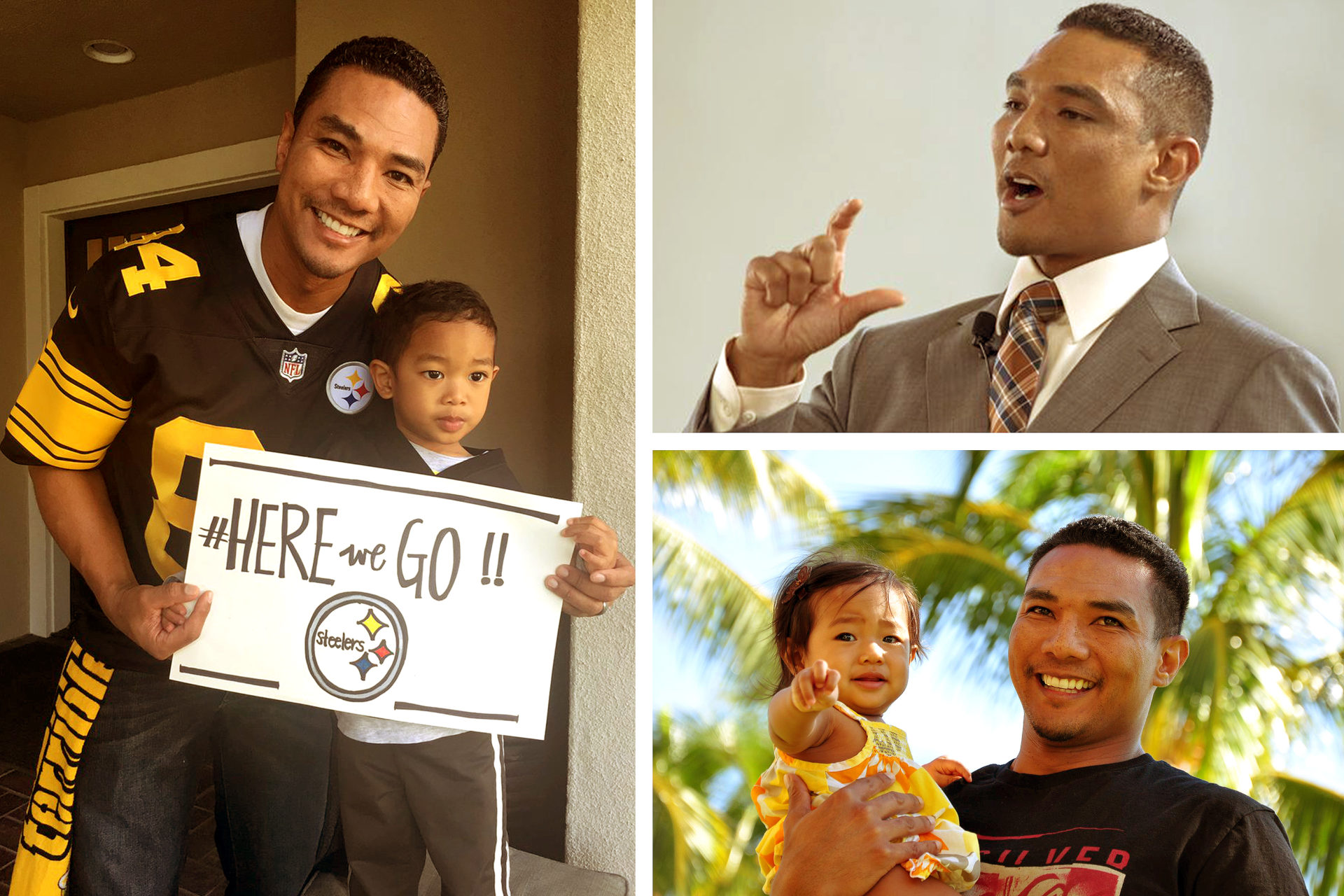

While there may not be breaks automatically added to his schedule, Foster makes sure he periodically takes time to check in with his two children. Maylea and Daylen, his 6-year-old son. He said they are mostly independent, but he takes turns with his wife to help them with their homework and daily needs.

Like many other parents, he’s been left confused trying to fill in as an elementary school teacher.

“Sometimes,” he said, “when I read my son’s homework, I’m wondering, like, what do they want us to do? It’s interesting in terms of understanding what their expectations are.”

Leadership isn’t new to Foster. It’s arguably what he’s been groomed to do his whole life. He was born in South Korea, his mother’s native land. His father, who is African-American, served in the U.S. Air Force.

Foster graduated Vacaville High in 1990 and went to UC Davis, becoming the first in his family to attend college. He played football four seasons for the Aggies, red-shirting his sophomore year in 1991. In 1993, Foster helped lead UC Davis to a 10-2 record and won the school’s first Division II playoff game in a decade. Foster shared the team’s Outstanding Back/Receiver Award with star running back Preston Jackson. In 1994, Foster was named a co-captain and the season culminated with him being given the team’s annual Bob Oliver Award, an honor bestowed upon the squad’s unsung hero.

By the way, Foster is a Pittsburgh Steelers fan.

Between football games and practices at UC Davis, he earned a bachelor’s degree in Applied Behavior Science. He went on to get a master’s degree from California State University, Long Beach in counseling and a doctorate degree from the University of Southern California in Higher Education Administration.

It was the EOP program — which helped him navigate college life at UC Davis by connecting him to available resources — that inspired him to get into student services. He wanted to support other first generation college students and expand the accessibility of college.

“I’m really passionate about equity,” he said in an earlier article for The Express, “and I’m passionate about underserved student populations, and first generation college students.”

Foster has found success wherever he’s gone. When he was at Rio Hondo College, he was named community college professional of the year for the western region by The Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs, and Administration — the Washington D.C. based nonprofit. When he was at Moreno Valley College it received a “Silver Seal” from the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge, a national program seeking to increase student voting. MVC pushed its voting turnout above 30 percent. More than 560 campuses have been involved in the All IN Challenge since 2016.

In February, Foster was accepted as a 2020 fellow by The Wheelhouse Institute, which aims to equip administrators with tools to improve the community college system. The acceptance essentially confirms Foster as a rising figure in the higher education scene.

Foster also served as the president of The African American Male Education Network and Development organization, also known as A2MEND, which is run by volunteering community college administrators and faculty to support underserved African-American males.

For more than two decades in education, Foster has built a reputation for leadership that gets results. Even before that, if you count his football days.

“I think,” Foster said, allowing himself a moment to envision the future, “we will be able to look back on it and say, ‘Wow, how did we get through this? How did we navigate this at that time?’ The learning that will occur with that reflection will be so impactful for me professionally and personally.”

Maybe all of that was preparation for this new, daunting challenge. Maybe he is just the one to deal with this, groomed unknowingly by his journey to LPC. Maybe he has the ideal personality, disposition and experience to guide the school through this and back to whatever the new normal will look like.

Then, he can get back to building relationships on campus, meeting students and connecting with his new terrain on the hills of Livermore. He can get back to executing his vision for the school and continue his track record of administrative success.

First, though, he has to get the college through this historic, world-altering reality.

“I just wanna say thank you to our faculty, our staff and our administrators for their commitment and dedication to our students during this time,” he said in what amounted to closing remarks in the interview. “I want to also applaud our students for their perseverance, for their dedication and commitment to their education. I want to wish everyone in the LPC community to stay healthy and safe during this outbreak. I look forward to everyone coming back together.”

He said goodbye and starts logging out of ConferZoom, and the last visual of the school’s new president was the same as the first. Foster was smiling.

Rebecca Robison is the news and campus life editor of The Express. Follow her @RebeccaRobiso19.