Nov. 9, 2009, was a normal day of construction at Las Positas campus.

Until metal hit bone.

Off of Loop Road on the Nature Valley Trail, at the west side of campus, a construction team worked to create a swale. This shallow basin for runoff water would be vital for managing rainwater. But a construction worker using a backhoe hit something unusual: bone.

News spread fast.

From the construction supervisor to LPC’s Maintenance and Operations (M&O), the findings sent one man from M&O running up the hill: Stan Barnes.

“‘You probably have five minutes to get pictures, so come right now,’” Carol Edson, emeritus geology laboratory technician at Las Positas, remembers Barnes saying.

Feeling the closing opportunity, Edson and Barnes sprinted back to the bones to find yellow tape and fencing proposals.

Edson dropped herself into the hole and started snapping pictures. But five minutes would have been a luxury. As Edson remembers it, she only had 30 seconds before being asked to get out.

They didn’t know at the time, but the construction workers had uncovered the remains of a Columbian mammoth, who lived between 20,000 and 100,000 years ago, said Edson.

Vertebrae and ribs were also uncovered in the process, but missing records meant that the other remains were not identified. More bones might remain on the Nature Valley Trail, according to Edson and Daniel Cearley, an anthropology professor at Las Positas and the author’s previous instructor. The goal of the exhumation, or removal of the bones, was animal identification. Paleontologists often exhume the minimum amount of bones necessary to the project goals, Cearley explained.

The bones hopped between the company formerly known as PaleoResource Consultants, which conducted research on the exhumed bones, to UC Berkeley’s Museum of Paleontology repository in Richmond. Here, the bones waited as Edson and Cearley worked on a multi-year repatriation, or repossession project.

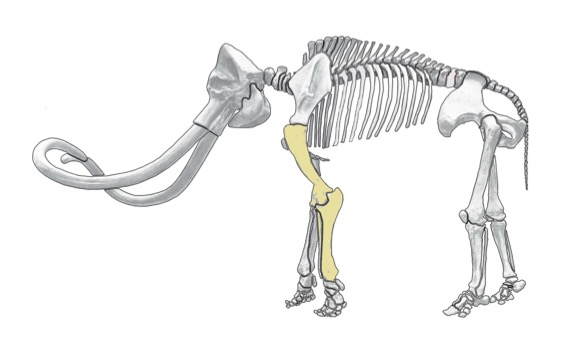

In 2019, after 10 years of planning and resourcing, Edson and Cearley brought three Columbian mammoth bones back home to Las Positas College: an upper arm bone and a fused radius and ulna from the animal’s left front leg. And in February 2021, the bones took stage in the clear cases of an exhibit in the college’s 1600 building.

According to Cearley, they have the potential to remind us of the creatures that lived tens and hundreds of thousands of years ago, ones whose remains exist beneath our feet: giant ground sloths, dire wolves and saber-toothed cats. They could invoke the curiosities of youth, inviting questions of all kinds, unbound by the imaginative restraints of our lifetimes. They could attract classes and the general public to an interactive learning experience.

These are the hopes project-spearheads, Edson and Cearley hold for the exhibit. The leaders still solicit feedback for the developing exhibit, wanting the Las Positas community to contribute to it. They look for new elements to add to the exhibit and suggestions for exhibit alterations, as the displayed posters are not finalized.

“Carol and Daniel brought it back to life,” Ann Kroll, prior Construction Manager during the swale construction project in 2009 said. Kroll is the current project planner/manager of the facilities/bond programs at Chabot-Las Positas Community College District. “They really want to present it. They really want it back on campus. And they have really been the stewards of trying to get this back.”

Three of the bones sit in clear viewing boxes, bottoms wrapped in a supportive plaster: a fused ulna and radius measuring over 3.5-feet long and upper arm bone measuring about 3-feet long, off-white in color. Posters affixed to the backgrounding wall describe the mysterious bones with the name Murray the mammoth.

The bones currently on display at Las Positas are on loan from UC Berkeley’s Museum of Paleontology for 5 years, meaning the first loan will end in 2024, but Edson doesn’t anticipate any issues with renewing this loan.

But repatriating these bones wasn’t easy. Before Edson and Cearley, this process has been uncharted territory for Las Positas College.

The two served as project advocates, from planning to enacting, even acting as the bone couriers when it was time to pick up the bones from the repository in spring 2019.

Far from the glamor of the Smithsonian in Washington D.C., the repository was just a nondescript warehouse in Richmond, CA. At least, that’s how it looked from the outside.

“You walk in there and it’s Wonderland,” Edson said. “It’s every kind of bone and thing you’ve ever imagined.”

The two signed a form, wrote the specimen’s numbers and rolled the bones from the repository to the back of a vehicle. Like an off-brand hearst for the long-dead, the ordinary car was fit with cardboard boxes to buffer the bones. Tarp and ties were armor against the bumping and twisting road to Livermore.

Broken bones for the departed don’t heal like those of the living, so every turn was a cautious one. The mammoth had already dealt with a few post-death breaks, a few of which were caused at the day of discovery.

Berkeley’s repository maintains some bones identified with the same number as the three loaned to Las Positas College. It is uncertain, at this point, whether or not these additional bones are from the same animal. Cearley explained water or land flows could carry different animal remains to the same resting place. This means, without the PaleoResource Consultants’ project report, the identity of the other bones is inconclusive.

For now, the exhibit includes only the bones definitively identified as belonging to a Columbian mammoth.

The exhibit goals are in-progress. As of March 2023, draft posters describing Murray’s life, death, and discovery line the exhibit’s back wall.

Edson and Cearley would like to purchase a life-sized vinyl image for an exhibit window: a Columbian mammoth towering 11-feet at shoulder-height in adolescence, like the one found on campus, or 13-feet at shoulder-height when full grown. “I want something life-sized,” Cearley said. “It would help stretch our imagination. I think that’s the idea: yank us out the ‘move here, A to B, get things done, how much time do I have?, time-is-money.’”

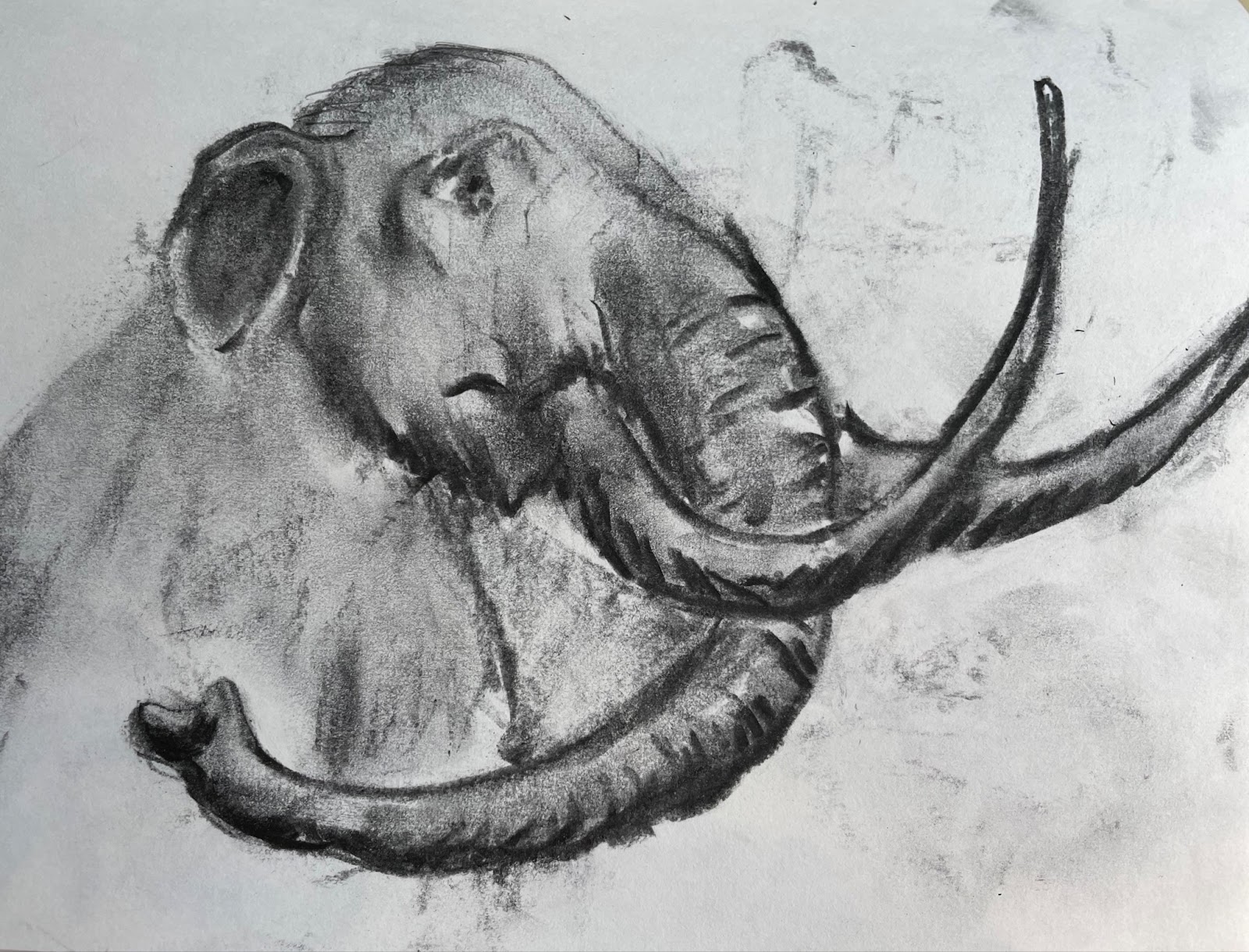

An oil on canvas mural of Columbian mammoths and the bones, currently being painted by Steve Newton, former geology faculty at Las Positas College, will also be displayed at the exhibit upon its undated completion.

“I hope they get a moment of recognition of being transported back to that time, of thinking about these sorts of scenes happening right on campus” Newton said. “You see the same hills in the same spots, but this was roamed by these giant beasts.”

Edson, Cearley, and the many other participating members of this display project continue to look for feedback on Murrary’s exhibit. They recognize that this exhibit and its place at Las Positas College is far from complete, rather, the project itself is dynamic.

Edson and Cearley encourage those interested to send comments and suggestions to cedson@laspositascollege.edu and dcearley@laspositascollege.edu, titling your email “Mammoth Project.”

“This mammoth (can) push our imagination into times that we rarely get an opportunity to see,” Cearley said. “The mammoth might be that conduit to create a relationship with the past that’s tangible, tactile, that we can visualize.”

Featured image at top of article: Daniel Cearley measuring the Columbian mammoth’s left upper arm bone at UC Berkeley’s Museum of Paleontology repository in preparation for loaning the bones. (Photo courtesy: Carol Edson and Dan Cearley)

Jude Strzemp is a freelance writer for the Express. Follow them @JStrzemp.